I’m taking the following as an axiom: Exposing real pre-emptive threading with shared mutable data structures to application programmers is wrong. …It gets very hard to find humans who can actually reason about threads well enough to be usefully productive.

When I give talks about this stuff, I assert that threads are a recipe for deadlocks, race conditions, horrible non-reproducible bugs that take endless pain to find, and hard-to-diagnose performance problems. Nobody ever pushes back.

October 26, 2009

Threading is Wrong

October 24, 2009

Ignorance is Moral Strength

I have long been impressed with the casino industry’s ability to, in the case of blackjack, convince the gambling public that using strategy equals cheating.

October 23, 2009

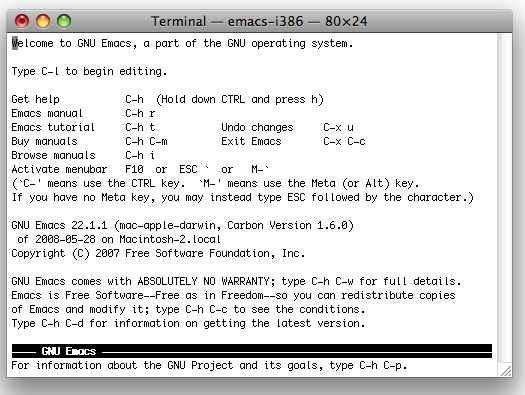

GUI is Dead, Long Live UI

The term GUI, Graphical User Interface, pronounced “Gooey” is laughably anachronistic. All interfaces meant for people on modern computers are graphical. The right abbreviation to use today is simply UI, for User Interface, pronounced “You I”.

Believe me, I understand that a command line interface is still useful today. I use them. I’m a programmer. I get the whole UNIX thing. Even without a pipe, a command-line is the highest-bandwidth input mechanism we have today.

But all command lines live inside a graphical OS. That’s how computers work in the 21st century.

Whenever I see “GUI” written I can’t help but wonder if the author is dangerously out of touch. Do they still think graphical interfaces are a novelty that needs to be called out?

October 22, 2009

iPhone Shows the Irrelevance of the Programmer User

There’s a lot of discord over Apple’s draconian “closed” handling of the iPhone and App store. And rightly so. But there are a few interesting lessons in the current situation. The one I want to discuss now is that,

Being able to program your own computer isn’t enough to make it open

As things stand today, Apple can’t stop you from installing any damn iPhone app if you build yourself.

To do that you have to join the iPhone developer program of course. And there’s a $99/year fee. That’s inconvenient, but it’s just using a subscription-based way of selling iPhone OS: Developer Edition.

That’s the kind of dirty money-grabbing scheme I’d expect from Microsoft. It’s a bit shady, because it’s not how most OSes are sold. But it’s not without precedent. And unless you are against ever charging money for software, I don’t think there’s an argument that it’s actually depriving people of freedom.

Yes, it’s an unaffordably high price for many. But the iPhone is a premium good that costs real money to build — it’s inherently beyond many people’s means, even when subsidized.

Observation: Only Binaries Matter

If you have a great iPhone app that Apple won’t allow into the store, you can still give it to me in source code form, and since I have iPhone OS: Developer Edition, I can run it on my iPhone.

But clearly that’s not good enough.

In fact, I’m not aware of any substantive iPhone App that’s distributed as source. By “substantive” I mean an app with a lot of users — say as many as the 100th most downloaded App Store app — or an app that does something that makes people jealous, like tethering (See update!), which we know is possible using the SDK. I realize this is a wishy-washy definition — what I’m trying to say is that distributed-as-source iPhone Apps seem to be totally irrelevant.

“It’s not open until I can put Linux on it”

I believe it’s technically possible to run Linux on an iPhone without jail-breaking it. (Although it’s not terribly practical.) Just build Linux (or an emulator that runs Linux) as an iPhone app, and leave it running all the time to get around the limitations on background processes.

Apple won’t allow such a thing into the App Store of course —but how does that stop you from distributing the source for it? As best I can tell, it doesn’t.

So as things stand today, yes you can distribute source code that lets any iPhone OS: Developer Edition user run Linux. It’s technically challenging, but it’s doable.

Conclusion

It’s possible to build open systems on top of closed systems. We’ve done it before when we built the internet on Ma Bell’s back.

But the iPhone remains a closed device. User-compiled applications have 0 momentum. And I think that clearly shows the irrelevance of the rare “programmer user”, who is comfortable dealing with the source code for the programs he uses.

UPDATE 2010-01-21: iProxy is an open-source project to enable tethering! Maybe the programmer-user will have their day after-all.

October 20, 2009

Knuth can be Out of Touch

…Knuth has a terrible track record, bringing us TeX, which is a great typesetting language, but impossible to read, and a three-volume set of great algorithms written in some of the most impenetrable, quirky pseudocode you’re ever likely to see.

There, it’s been said. But let the posse note I wasn’t technically the one to do it!

JavaScript Nailed ||

One thing about JavaScript I really like is that its ||, the Logical Or operator, is really a more general ‘Eval Until True‘ operation. (If you have a better name for this operation, please leave a comment!) It’s the same kind of or operator used in Lisp. And I believe it’s the best choice for a language to use.

In C/C++, a || b is equivalent to,

if a evaluates to a non-zero value:

return true;

if b evaluates to a non-zero value:

return true;

otherwise:

return false;

Note that if a can be converted to true, then b is not evaluated. Importantly, in C/C++ || always returns a bool.

But the JavaScript || returns the value of the first variable that can be converted to true, or the last variable if both variables can’t be interpreted as true,

if a evaluates to a non-zero value:

return a;

otherwise:

return b;

Concise

JavaScript’s || is some sweet syntactic sugar.

We can write,

return playerName || "Player 1";

instead of,

return playerName ? playerName : "Player 1";

And simplify assert-like code in a perl-esq way,

x || throw "x was unexpectedly null!";

It’s interesting that a more concise definition of || allows more concise code, even though intuitively we’d expect a more complex || to “do more work for us”.

General

Defining || to return values, not true/false, is much more useful for functional programming.

The short-circuit-evaluation is powerful enough to replace if-statements. For example, the familiar factorial function,

function factorial(n){

if(n == 0) return 1;

return n*factorial(n-1);

}

can be written in JavaScript using && and || expressions,

function factorial2(n){ return n * (n && factorial2(n-1)) || 1;}

Yes, I know this isn’t the clearest way to write a factorial, and it would still be an expression if it used ?:, but hopefully this gives you a sense of what short-circuiting operations can do.

Unlike ?:, the two-argument || intuitively generalizes to n arguments, equivalent to a1 || a2 || ... || an. This makes it even more useful for dealing with abstractions.

Logical operators that return values, instead of simply booleans, are more expressive and powerful, although at first they may not seem useful — especially coming from a language without them.

October 19, 2009

Less is More

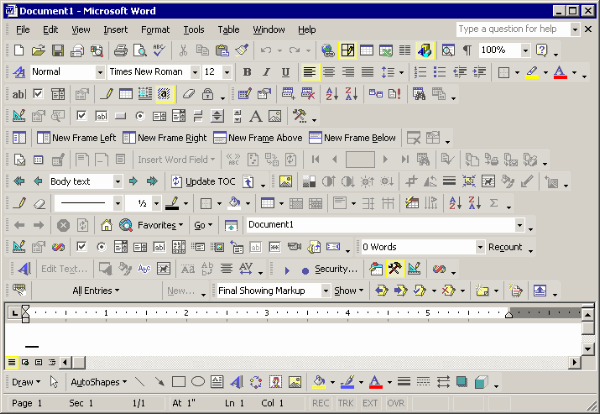

Fundamentally, a computer is a tool. People don’t use computers to use the computer, they use a computer to get something done. An interface helps people control the computer, but it also gets in their way. Inevitably, any on-screen widget is displacing some part of the thing the user is trying to manipulate.

As an infamous example, expanding Microsoft Word’s toolbars leaves no room for actually writing something,

(Screenshot by Jeff Atwood)

Users don’t want to admire the scrollbars. Truth be told, they don’t even want scrollbars as such, they just want to access content and have the interface get out of the way.

Show The Data

I highly recommend Edward Tufte’s The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. It’s probably the most effective book or cultivating a distaste for graphical excesses.

Tufte’s teachings are rooted in static print. But many of the principles are just as valuable in interactive media. (And static graphics are still very useful in analysis and presentation. Learning how to graph better isn’t a waste of time.)

Tufte’s first rule of statistical graphic design is, “Show the data” , and it’s an excellent starting point for interface design as well.

Cathy Shive has an excellent post expanding on Tufte’s term Computer Administrative Debris.

The Chartjunk blog showcases a few real-world examples of Tuftian redrawings.

Get Out of My Mind

Learning happens when attention is focused. … If you don’t have a good theory of learning, then you can still get it to happen by helping the person focus. One of the ways you can help a person focus is by removing interference.

–Alan Kay, Doing With Images Makes Symbols.

Paradoxically then, the better the design, the less it will be noticed. We should strive to write our interfaces in invisible ink.

sizeof() Style

Never say sizeof(sometype) when you can say sizeof(a_variable). The latter works even if the type of a_variable changes, and it is much more obvious what the size is supposed to represent.

October 16, 2009

Shaving Soap Reviews

I sometimes shave with a straight razor, and always use an old-fashioned brush and mug of soap.

I try to review every shaving soap I try. So far I have short reviews for over a two dozen shaving soaps. (Those reviews are totally affiliate-free and self-funded, by the way.)

The biggest thing I’ve learned doing this (besides the unfortunate fact that most soaps irritate my skin) is to always, always, always date anything you write. Tastes change with time. Soap formulations change with time. Availability and price change with time. Dates are hugely helpful at deciding if a bit of information is still relevant. Sadly, I learned this the hard way — most of my reviews are undated. When I claim that two soaps are both the “best” there’s no way to know which is the more informed superlative.

Here’s the short list of soaps I always try to have on hand (most-preferred first):

Hack: Counting Variadic Arguments in C

This isn’t practical, but I think it’s neat that it’s doable in C99. The implementation I present here is incomplete and for illustrative purposes only.

Background

C’s implementation of variadic functions (functions that take a variable-number of arguments) is characteristically bare-bones. Even though the compiler knows the number, and type, of all arguments passed to variadic functions; there isn’t a mechanism for the function to get this information from the compiler. Instead, programmers need to pass an extra argument, like the printf format-string, to tell the function “these are the arguments I gave you”. This has worked for over 37 years. But it’s clunky — you have to write the same information twice, once for the compiler and again to tell the function what you told the compiler.

Inspecting Arguments in C

Argument Type

I don’t know of a way to find the type of the Nth argument to a varadic function, called with heterogeneous types. If you can figure out a way, I’d love to know. The typeof extension is often sufficient to write generic code that works when every argument has the same type. (C++ templates also solve this problem if we step outside of C-proper.)

Argument Count (The Good Stuff Starts Here)

By using variadic macros, and stringification (#), we can actually pass a function the literal string of its argument list from the source code — which it can parse to determine how many arguments it was given.

For example, say f() is a variadic function. We create a variadic wrapper macro, F() and call it like so in our source code,

x = F(a,b,c);

The preprocessor expands this to,

x = f("a,b,c",a,b,c)

Or perhaps,

x = f(count_arguments("a,b,c"),a,b,c)

where count_arguments(char *s) returns the number of arguments in the string source-code string s. (Technically s would be an argument-expression-list).

Example Code

Here’s an implementation for, iArray(), an array-builder for int values, very much like JavaScript‘s Array() constructor. Unlike the quirky JavaScript Array(), iArray(3) returns an array containing just the element 3, [3], not an uninitilized array with 3 elements, [undefined, undefined, undefined]. Another difference: iArray(), invoked with no arguments, is invalid, and will not compile.

#define iArray(...) alloc_ints(count_arguments(#__VA_ARGS__), __VA_ARGS__)

This macro is pretty straightforward. It’s given a variable number of arguments, represented by __VA_ARGS__ in the expansion. #__VA_ARGS__ turns the code into a string so that count_arguments can analyze it. (If you were doing this for real, you should use two levels of stringification though, otherwise macros won’t be fully expanded. I choose to keep things “demo-simple” here.)

unsigned count_arguments(char *s){

unsigned i,argc = 1;

for(i = 0; s[i]; i++)

if(s[i] == ',')

argc++;

return argc;

}

This is a dangerously naive implementation and only works correctly when iArray() is given a straightforward non-empty list of values or variables. Basically it’s the least code I could write to make a working demo.

Since iArray must have at least one argument to compile, we just count the commas in the argument-list to see how many other arguments were passed. Simple to code, but it fails for more complex expressions like f(a,g(b,c)).

int *alloc_ints(unsigned count, ...){

unsigned i = 0;

int *ints = malloc(sizeof(int) * count);

va_list args;

va_start(args, count);

for(i = 0; i < count; i++)

ints[i] = va_arg(args,int);

va_end(args);

return ints;

}

Just as you'd expect, this code allocates enough memory to hold count ints, and fills it with the remaining count arguments. Bad things happen if < count arguments are passed, or they are the wrong type.

Download the code, if you like.

Parsing is Hard, Let's Go Shopping

I didn't even try to correctly parse any valid argument-expression-list in count_arguments. It's non trivial. I'd rather deal with choosing the correct MAX3 or MAX4 macro in a few places than maintain such a code base.

So this kind of introspection isn't really practical in C. But it's neat that it can be done, without any tinkering with the compiler or language.