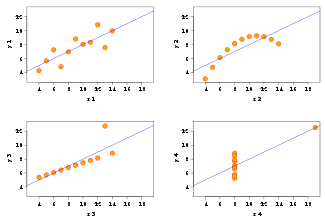

You’re looking at Anscombe’s quartet: 4 datasets with identical simple statistical properties (mean, variance, correlation, linear regression); but obvious differences when graphed.

(via Best of Wikipedia)

Graphs aren’t a substitute for numerical analysis. Graphs are not a panacea. But they’re excellent for discovering patterns, outliers, and getting intuition about a dataset. If you never graph your data, then you’ve never really looked at it.

War Story

I was working on optimizing color correction, using SSE (high performance x86 instructions). One operation required division — an expensive operation for a computer. The hardware had a divide instruction, but sometimes using the Newton-Raphson method to do the division in software is faster. You never know until you measure.

While doing the measurement, I somehow got the crazy idea to try both: I’d already unrolled the inner loop so instead of repeating the divide or Newton’s Method twice, I’d do a divide and then use Newton’s Method for the next value. Strangely enough, this was faster on the hardware I was benchmarking than either method individually. Modern hardware is a complex and scary beast.

I was fortunate enough to have a suite of very good unit tests to run against my optimized code. But there was a caveat to testing correctness. Because computers don’t have infinitely precise arithmetic, two correct algorithms might give different answers — but if the numbers they gave were close enough to the infinitely precise answer (say a couple ulps apart) it was good enough. (We can only be exact within some Tolerance!) The tests cleared my hybrid divide/Newton-Raphson function: but we couldn’t use it, because it was fundamentally broken.

Even though the error was acceptably small, it had a nasty distribution. Using divide gave color values that were a bit too light. Doing a divide in software gave values that were a bit too dark. Individually these errors were fine. Randomly spread over the image they would have been fine. But processing every other pixel differently had the effect of adding alternating light/dark stripes! We see contrast, not absolute color, so the numerically insignificant error was quite visible. Worse still, bands of 1 pixel stripes combined to form a shimmering Moiré pattern. It was totally busted. Unusable.

This was all immediately obvious when the results of the color correction were “graphed”. Actually looking at the answer caught a subtle error that our suite of unit tests missed.

To be clear, more subjective graphical analysis is not a substitute for numerical analysis and data mining. But I believe in actually looking at your data at least once. A graph is a kind of end-to-end visualization of everything, and that has value. Graphs are a cheap sanity check — does everything look right? And sometimes, they can give you real insight into a problem.